“Equality Is not Achieved by Accepting the Status Quo”

Q: If you could describe yourself in 150 words, what would you say?

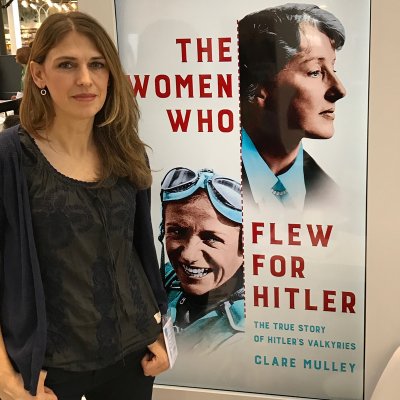

A: My professional bio says that ‘Clare Mulley is the award-winning author of The Woman Who Saved the Children, which won the Daily Mail Biographers' Club Prize, and The Spy Who Loved, now optioned by Universal Studios. Clare's third book, The Women Who Flew for Hitler, is a dual biography of two extraordinary women at the heart of the Third Reich, but who ended their lives on opposite sides of history.

A regular contributor to TV and radio, Clare recently gave a TEDx talk at Stormont, and lectures in London and Paris on wartime female special agents. She reviews non-fiction for the Telegraph, Spectator and History Today. Clare was chair of the judges for the Historical Writers Association 2017 Non-Fiction Prize, and has recently become an honorary patron of the Wimpole History Festival.’

To take it to 150 words, I might add that I love walking, talking and eating roast potatoes.

Q: Your work as a writer and historian on women is inspiring. Could you tell us more about your story and how you came to the work you are doing now?

A: Thank you.

I had always wanted to write, but could never come up with good enough plots. So instead, after working overseas for a few years, I threw myself into useful jobs like raising funds for Save the Children. While there, I discovered the charity’s founder, the inspirational Eglantyne Jebb.

There is so much to love about Jebb. She refused to meet the polite expectations placed on an Edwardian lady but went off to deliver aid and investigate war crimes in the Balkans when it was already a war-zone in the run-up to the First World War. She imported and translated enemy newspapers during the war; and was arrested in Trafalgar Square in 1919 while campaigning against the Liberal government’s policy to continue the economic blockade to Europe after the armistice. Having conducted her own defence in court, Jebb launched Save the Children to help the youngest and most vulnerable in Germany and Austria when these were still considered enemy nations. She went on to write the first statement of children’s human rights that has since evolved into the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, now the most universally accepted human rights instrument in history. Yet Jebb was not fond of individual children, ‘the little wretches’ as she once called them.

I fell for her immediately. She gave me a plot, character development, even dialogue in her wonderful, often dryly funny, articles and letters. I was not a novelist, I discovered, but a biographer!

"What we choose to include, and how we tell our history, informs our sense of identity, our values and understanding of our place in the world"

Other challenges are more strictly professional. Conducting research is hugely rewarding but often requires budget, languages and contacts I don’t (yet) have.

Researching the life of Krystyna Skarbek, aka Christine Granville, the first woman to serve Britain as a secret agent during the Second World War, for my biography The Spy Who Loved, contained inherent difficulties – it’s that word ‘secret’. Agents were taught not to leave a paper trail, and Skarbek was good at covering her tracks. When I started researching her life there were only three known letters in her hand. Letters are like the fossils of emotion, capturing the intangible nuances of character that would otherwise be lost to us. Fortunately, many more letters were waiting to be discovered, giving us a fascinating new insight into her character.

Finally, my last book looks at two remarkable women, Hanna Reitsch and Melitta von Stauffenberg, the only female test-pilots to serve the Nazi regime, although they had deeply opposing political views. Writing about a regime responsible for the deaths of many millions presented very different challenges. The Women Who Flew for Hitler asks why these two brilliant and courageous pilots, both with a strong sense of honour and duty, chose to serve that regime, and in one case to then fight against it. I hope that what the book reveals, the good and the bad, will help contribute towards a better understanding of how Hitler was able to harness the resources of his country for his terrible ends.

Q: What can we learn from strong women throughout history? How might these lessons be applied to the struggles of today?

A: ‘Strong women’ are of course a diverse group, but women have faced some consistent challenges in patriarchal societies across time and place. Some have responded by fighting for ‘equal but different’ status, others for equality of opportunity. Some have seen themselves as champions for their gender, others as exceptions to the rule, and some have paid no heed at all to convention or the breaking of it.

Lessons are varied, therefore, responding to context, character and opportunity, but at another level the message is simple. Equality is not achieved by accepting the status quo.

Q: What significance might the use of narrative or storytelling hold in addressing global issues?

A: ‘History’, I believe, is not so much the past, as our understanding of the past. As such our history is constantly evolving, being revised both as new evidence is uncovered, and as we reassess what we think we know. What we choose to include, and how we tell our history, informs our sense of identity, our values and understanding of our place in the world, as individuals, social groupings, and nations.

It is a cliché that those who do not know history are doomed to repeat it, but it is true that whether or not we choose to learn the lessons of the past, our present decisions and actions are informed by our understanding of that past; in a sense it forms our character. Revising how we see our history to include the presence, voices and stories of, for example, women in war, children in pre-history or Muslims in Tudor England, gives us a much richer understanding of the world, our place in it, and human ability to respond to changes and challenges.

Q: Can you share with us a couple of stories that have either inspired you or transformed the way you think/act?

A: I have been deeply inspired by the decisions and actions of both Eglantyne Jebb and Krystyna Skarbek.

Never fond of individual children, Jebb is sometimes considered an unlikely children’s champion. She chose to focus on the welfare and rights of children because they were among the most vulnerable in Europe in 1919, and because supporting children was an investment in the future – she wished to strengthen international relations as a way to heal the world after the trauma of the First World War. Jebb also recognised that the image of the ‘innocent child’ lent itself to the public imagination, and she exploited both this and the maternal image that others attributed to her, to support her cause. ‘To succeed in life,’ she once wrote, ‘we must give life.’ But Jebb chose to give life on her own terms by establishing Save the Children in 1919, and then championing the then revolutionary concept of children having human rights. In doing so she saved the lives of many thousands in her lifetime, and many millions since. A woman before her time, she had the imagination, determination and pragmatism to change the way the world both regards and treats its children. Yet her name is hardly known today.

Inspired by Jebb, I have become a social historian, focusing mainly on the rich seam of untold stories of remarkable women in our history. I also continue to support the wonderful work of Save the Children.

Krystyna Skarbek was not only the first woman to work for Britain as a special agent in the Second World War, but also the longest serving. It was still 1939 when this Polish-born countess banged on the door of the British secret services and not so much volunteered, as demanded to be taken on. It would be some years before any other women were deployed as special agents, and then partly in response to Skarbek’s successes.

They came from many different countries and included Christians, Jews and Muslims as well as atheists among their number. What is significant is their diversity, rather than their conformity to any beauty standard or anything else.

Furthermore, Skarbek was extremely good at her job. Among her achievements, she smuggled out the first film evidence of preparations for Operation Barbarossa, the Nazi German invasion of their erstwhile ally, the Soviet Union, to land on Churchill’s desk. In occupied France, she made the first contact between the French resistance on one side of the Alps and the Italian partisans on the other, and later secured the defection of an entire Nazi German garrison on a strategic pass in those mountains. She also single-handedly saved the lives of three of her male colleagues just hours before they were due to be shot. For her contribution to the Allied war effort, Skarbek was awarded the George Cross, the OBE, and the French Croix de Guerre. Yet, like Jebb, Skarbek has been largely forgotten.

These women taught me not just about determination, courage, and the importance of imagination and action, but also about how our national record has been written, and why it needs to be reassessed and represented! It has been a real joy, as well as an honour, to help bring their stories and others to light and so contribute to changing this narrative.

Q: Can you talk about one woman who has impacted your life?

A: Many women regularly inspire me, both historical subjects, and friends, family and other figures today from campaigners like Gina Miller and historians like Mary Beard, to the brilliant and dedicated teachers at my daughters’ schools. I could not write the books I do without the example, support and ongoing work of so many other women. It feels impossible to single out one person and, in any case, it is the collective endeavour that is so encouraging.

Q: What have been the most important lessons you have learned from your role as a leading scholar in women’s history?

A: I am not a leading scholar, but I have hugely enjoyed helping to bring the extraordinary stories of a number of remarkable women to light, not just as ‘women’s history’ but as part of the general historical narrative. For me the key lessons have been around questioning everything, reading as much as possible, working hard, accepting and giving help, being resilient and enjoying what I do.

Ultimately your work will be judged on its own merits, so research and write the books that you would like to read, and that make you proud of your contribution.

Q: Do you believe it is the era of women and why?

A: All eras surely belong to all people, it just depends on what perspective you choose to take.

If this question relates to female power, however, then we are currently witnessing another wave of feminism in the west, building on the work of women before us. The #MeToo movement has gained momentum; there is a new drive for equal pay for equal work; and increasing recognition of the female contribution in the arts, business and the public sector. As a feminist I was recently deeply inspired to see the first statue of a woman, the leading suffragist Millicent Fawcett, unveiled in Parliament Square. ‘Courage Calls to Courage Everywhere’, says the banner she is holding towards the House of Commons.

We need courage, as there is still a long way to go before we have anything like equality of recognition, respect and opportunity in Britain and elsewhere. Fawcett’s statue is symbolic but across Britain, there are still more statues to men named John than to non-royal, non-fictional women at all, and men still dominate in every sector of society. I have managed to organize a bronze bust of Krystyna Skarbek, which can be seen at Ognisko Polskie, the Polish Club in London’s South Kensington, and I would love there to be one for Eglantyne Jebb. Another woman who deserves a statue is Mary Wollstonecraft whose inspirational book, A Vindication of the Rights of Women, was published in 1792, but is still very relevant today. ‘I do not wish women to have power over men’, Wollstonecraft wrote, ‘but over themselves’. That remains a necessary fight all around the world.

Clare Mulley

Award-winning Author

Clare Mulley is the award-winning author of The Woman Who Saved the Children, which won the "Daily Mail" Biographers' Club Prize, and The Spy Who Loved, now optioned by Universal Studios.

Clare's third book, The Women Who Flew for Hitler, is a dual biography of two extraordinary women at the heart of the Third Reich, but who ended their lives on opposite sides of history. A regular contributor to TV and radio, Clare recently gave a TEDx talk at Stormont, and lectures in London and Paris on wartime female special agents. She also reviews non-fiction for the Telegraph, Spectator and History Today. Clare was chair of the judges for the Historical Writers Association 2017 Non-Fiction Prize, and has recently become an honorary patron of the Wimpole History Festival.

Published: 11/06/2018